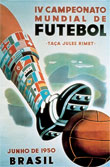

The 1950 FIFA World Cup was the first since 1938, mostly because of an intercontinental dust-up commonly known as World War II. Brazil was selected to host the tournament on the back of a third-place performance in the previous World Cup, and it was eagerly anticipated by the newly democratic country, which was looking to establish itself as a global power, in football and otherwise. The mayor of Rio de Janeiro was able to push forward construction  of a controversial stadium named after the Maracanã neighbourhood, opening it about a week before the World Cup began.

of a controversial stadium named after the Maracanã neighbourhood, opening it about a week before the World Cup began.

Now, the World Cup wasn’t always set up the way it is now, with the playoff round leading to an ultimate final. This World Cup consisted of two round-robin group stages. The first, similar to the group stage we’re familiar with today, featured four groups consisting of four teams each—at least, they consisted of four teams each before Scotland, India and Turkey withdrew from the competition. The second stage of the tournament was a single group made up of each group’s winners: Brazil, Spain, Sweden, and  Uruguay. Uruguay’s group in the first round originally contained Scotland and Turkey, so the 1930 world champions only played one game to qualify out of their group, defeating perennial minnows Bolivia.

Uruguay. Uruguay’s group in the first round originally contained Scotland and Turkey, so the 1930 world champions only played one game to qualify out of their group, defeating perennial minnows Bolivia.

Brazil won their first two games of the final group handily, thrashing Sweden and Spain (7-1 and 6-1, respectively). Uruguay, by contrast, could only draw with Spain and eke out a 3-2 victory over Sweden. Heading into the final game of the tournament against Uruguay at the Maracanã, Brazil were heavy favourites. As Alex Bellos notes in his masterful book on Brazilian football, Brazil had a good record against Uruguay in their recent matches, winning two of a three-match series held in Rio two months before the World Cup. The day before the match, Brazil’s newspapers anointed their countrymen as champions, saying “Tomorrow we will beat Uruguay!” and printing pictures of the national team accompanied by the words “These are the world champions.” The final is suspected to have attracted 200,000 spectators to the Maracanã, many of whom did not pay for a ticket.

Just after halftime, Brazil took the lead through Friaça. Pepe Schiaffino equalized for Uruguay in the 66th minute, but because of the nature of the round-robin competition, Brazil only needed a draw to win the tournament. The score held at 1-1 as the match headed into the final 15 minutes, and for Brazil, the World Cup seemed as good as won.

“Only three people have, with just one motion, silenced the Maracanã: Frank Sinatra, Pope John Paul II, and me.” —Alcides Ghigghia

Alcides Ghigghia scored for Uruguay in the 79th minute. Brazil could not manage a response. It was 2-1 in Uruguay’s favour, and no one could do anything about it. The champions were dead. Long live the champions.

“Ghigghia’s goal was received in silence by all the stadium. But its strength was so great, its impact so violent, that the goal, one simple goal, seemed to divide Brazilian life into two distinct phases: before it and after it.” —Joáo Máximo

My history professor often insisted that we cannot understand anything without first understanding its context. We cannot understand something in a vacuum, stripped of any substance or frame of reference. Perhaps more importantly, we cannot allow our own modern conceptions and opinions to cloud our view. Perhaps this is why Pelé seems less spectacular to us: because we live in a world of Ronaldinhos and Robinhos and Neymars. A world of YouTube football and Nike-branded stepovers.

My history professor often insisted that we cannot understand anything without first understanding its context. We cannot understand something in a vacuum, stripped of any substance or frame of reference. Perhaps more importantly, we cannot allow our own modern conceptions and opinions to cloud our view. Perhaps this is why Pelé seems less spectacular to us: because we live in a world of Ronaldinhos and Robinhos and Neymars. A world of YouTube football and Nike-branded stepovers.

1950 is Pelé’s context. Pelé is post-Ghigghia. He was still a boy in 1950, dribbling a grapefruit through the streets of Bauru while a country crumbled around him. He wasn’t even in his hometown club’s youth system until 1952, and he joined Santos four years later. The canvas that Pelé was given was warped with frustration. In 1954—three years before Pelé would make his international debut—Brazil was dumped out at the World Cup’s first knockout stage by Hungary’s Mighty Magyars. They were, hard as it is to believe, chokers on the big stage.

Before Pelé, no one used the phrase “jogo bonito” or “samba football” to describe the Brazilian national team. Pelé was the head author of those myths, the creator of that particular brand, fashioning the lasting image of Brazilian football out of the ashes of 1950. When Alan and Brian talk about “seeing” Pelé,” I must admit to myself that maybe I never will truly see Pelé. Certainly not as Brazil saw him in 1958, a teenager pulling his country out of its tortured history. Or as the world saw him in 1970, in the new vibrancy of colour television, playing a vital part in some of the most impressive football the planet had ever seen. I can see him now, casually stroking the ball out in front of the onrushing Carlos Alberto, I can sit in awe of the nonchalance with which he creates arguably the greatest goal ever scored in a World Cup. Somehow, though, it’s not the same thing. My desk is not the Azteca, nor is it Råsunda. I did not experience the Maracanazo, and that is not my frame of reference. You and I live in a world that has been, in part, created by Pelé: His influence may not be immediately apparent in the style of contemporary players, but it’s visible everywhere in the landscape in which those players play. Maybe we can’t see Pelé, but we are richer because Pelé was seen.

Gareth Simpson writes for the football blog 7500 to Holte. You can find him more regularly and less seriously on Twitter.

Read More: Pelé

by Gareth Simpson · August 21, 2010

[contact-form 5 'Email form']